Europe is now more than half a year into the coronavirus pandemic, having spent the first quarter of 2020 watching helplessly as the disease swept across China and the east. As the outbreak arrived here we saw border closures and travel restrictions, enforced working from home and limits on social contact. As elsewhere, European economies took a pounding.

So, how have markets reacted? Leadership was at first defensive, led by technology and pharmaceuticals, and this persisted until value stocks hit their nadir on 18 May.1 June saw the market rebound broaden. Price/earnings ratios of banks and “value cyclicals” had hit rock-bottom, which was not sustainable.

Up to the end of April, many active managers outperformed the index because they were defensively positioned, and in this phase there was no apparent disconnect: investors were cautious and data was bad. But more recently equity markets have decoupled from fundamental economics, particularly in the US.

Cyclical stocks were terrible performers until mid-May but then bounced back: in a month the banks sub-index recovered by 30%. Food and beverages, which earlier benefited from being in the defensive camp, became the worst performing sector and mining and financials the best. In that period, value-oriented stocks unwound most of the losses and year-to-date returns turned positive. Asian markets were the most extreme movers, as relative performance of these stocks completely reversed.2

Some see this as more than tactical, but we are not so sure. The correlation of value-versus-growth with other factors can be ranked: firstly with bond yields, then PMI momentum (purchasing managers index, a measure of economic trends), then with the US dollar, then the oil price. For a rotation to last it needs help from these factors, yet the main job of the US Federal Reserve now is to keep bond yields under control.

So, the rotation is stalling because bond yields have stalled. And while PMI momentum suggests a V-shaped recovery, as does recent market performance, we are still 20% behind the old norms,3 so we are also seeing the second factor: activity momentum rolling over.

Losing momentum

In January, before the Covid-19 crisis, the first phase of the US-China trade deal was signed and Phase Two was imminent. It seemed President Trump and China were playing ball and that Trump was a dead-cert for a second term. Then the crisis hit and economic data collapsed. The last month has seen an uptick, but that trend is not going to accelerate from here. US retail sales for May were up 17% year-on-year, a huge rebound – but they had fallen 15% in April. Weekly same-store sales growth has since turned down again.4

Figure 1 shows the New York Fed weekly economic index rolling over. So the economic surprise index seems to have peaked and may deteriorate from here. The PMI fell to 20 before bouncing back to 50, but it is probably too late to hope for further outperformance from financials and cyclicals.

Source: Bloomberg/Federal Reserve Bank of New York, July 2020.

True, demand is pent-up – for example, it was simply impossible to buy any car or a property in the middle of shutdown and now we are playing catch-up – and will bounce, but crucially it will lack sustainable momentum. Chinese car sales, for example, recently showed a fall of 17% over four weeks and are now back to March’s levels.5 They were helped by central bank and fiscal support, but to believe this trend continues would imply higher bond yields and an (unlikely) acceleration in the growth rebound.

Employment fallout

The market is currently discounting a V-shaped recovery, but we believe job losses endanger this. As economies reopen, jobs data will get worse. Higher unemployment will damage sectors that rely on crowds – leisure, hospitality and retail – as they will have a reduced capacity. The hit to the global economy will be at least 10% as we emerge from the crisis – the IMF estimates $10 trillion will be cut from an $85 trillion global economy.6 All this is a real danger for service-oriented economies like the UK, as well as of course the US.

So, with 10% of GDP lost and the labour market impaired, there is no chance of 2% inflation, so the 10-year yield will be nailed to zero. PMI data, meanwhile, shows China was first in and out of this downturn. In March, when the Chinese PMI rallied from 30 to 50, bank shares rose 35%, but they are now back to their relative lows.7 In 2009, money supply growth accelerated and cyclicals bounced hard; the same happened in 2016. But Chinese money supply now is telling us we cannot rely on cyclicals performing from here

So, if bond yields and PMIs cannot rise, and Chinese money supply is stagnating, thus hampering value and cyclical stocks, what stocks will benefit?

The corollary of damaged cyclical sectors is that we can expect resumed outperformance from technology and pharmaceuticals. With inflation and interest rates nailed to the floor, it is hard to argue against defensive growth stocks. Depressed bond yields compress the discount rate, favouring long-duration assets with high and sustainable cashflows. The PE relative of European consumer staples is at a 10-year low,8 and the same argument holds good for utilities, technology, healthcare and other long-duration assets.

Looking ahead

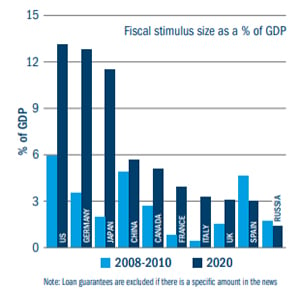

One of the side-effects of the collapse in interest rates is that governments are incentivised to borrow just as economies most need support. Figure 2 shows a far higher fiscal response to the coronavirus than in the global financial crisis of 2008/09. With this mixture of low interest rates and massive fiscal easing, it is no surprise that equities have bounced so hard.

Source: BCA Research, July 2020.

If Joe Biden wins the presidential election, a potential reversal of the Trump tax cuts might cut S&P 500 earnings. However, domestic change is hard to achieve in the US – just look at Trump’s failed repeal of Obamacare – so under Biden the tax cuts may only be partially reversed. What does this mean for the dollar? The Fed balance sheet versus that of the rest of the world correlates with the dollar, so a burgeoning balance sheet and weakening dollar pose risks to trade. Has the dollar been going down because of the Fed’s credit impulse or because of reflation? It’s hard to say.

If earnings take five years to recover to the pre-virus trend, the present value of equities should be lower. But interest rates have been slashed everywhere and 10-year and 30-year yields crushed. A lower discount rate suggests higher not lower equities.