With monetary policy seemingly reaching the limits of its effectiveness, another approach is required for the continent to avoid ‘Japanification’. We believe a focus on productive sustainable investment could not only stimulate growth, but also bring about social and environmental benefits.

The eurozone’s slow growth, low inflation and low interest rates are increasingly a concern for analysts. Much has been written about “Japanification” or the “limits” and “side effects” of monetary policy, but less about alternative ways to avoid these outcomes. We believe that with a bit of thinking outside the box, and a focus on environmental and social issues, a mechanism exists to restart economic growth.

Tackling the financial crisis

Let’s rewind a little to look at why we are making comparisons with Japan. Both the eurozone and Japan are bank funded economies, so the monetary policy transmission mechanism is via the banking sector. When interest rates get to ultra-low levels, the banking sector ceases to function properly and the transmission mechanism stops working as effectively.

When Japan’s banks started to fail in the late 1990s, failure to recognise losses left the banking sector with a capital (supply-side) problem, so it couldn’t provide loans. There was also a demand-side problem. The private sector hadn’t deleveraged, needed to pay down debt and was reluctant to borrow. The country’s ageing demographic played into this, with older people more likely to save than borrow.

As quantitative easing was introduced, loan rates fell and bank net interest margins continued to be squeezed (ie, the difference between the interest paid on deposits and the interest charged on loans). With returns on equity (ROE) of 4%-5%, the banking sector could not earn its cost of capital by lending to the domestic economy1. The monetary policy transmission mechanism ceased to function effectively, and lending didn’t get to the private sector.

Within Europe there are bright spots in the banking industry, especially in France and the Netherlands. However, in southern Europe banks are still in repair mode and demand for loans remains anaemic. Negative rates and ultra-loose policy are pressuring net interest margins and could reduce average bank ROEs to 5% over the next two years. When similar demographics are considered, the direction of travel is eerily similar to Japan.

Without innovative thinking and the use of other policy tools we face a situation in which an impaired banking system fails to transmit credit to those areas in need. So what can be done?

Thinking outside the box: time for a green refinancing operation?

Accelerating banking union would encourage consolidation in the sector which would reduce costs, improve profitability and free up more capital for lending. Meanwhile, enhancing the capital markets union to allow households and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to be funded through the securitisation market could have a powerful effect on growth. However, both these projects have been moving at a snail’s pace.

Additionally, the European Central Bank could act more swiftly. Under the targeted longer-term refinancing operation (TLTRO) the ECB provides the banking sector with loans at negative interest rates if banks use those funds to lend to the non-financial private sector, principally SMEs. Extending the scheme to target green lending through a green refinancing operation (GRO) at an even more beneficial rate would allow banks to offer cheap financing to companies pursing green and sustainable objectives.

This could be enhanced by allowing the regulator to assign lower risk weightings to these loans as the lending helps mitigate the financial impact of future climate risks. Banks would then have a dual incentive to make these sorts of loans. However, the central bank cannot act alone here; this would require co-ordination between governments and regulators.

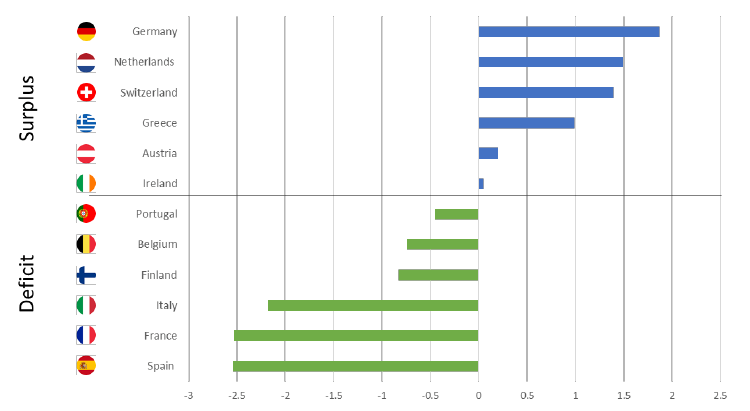

The most suitable option to stimulate the economy, we think, is fiscal. While traditional fiscal easing might exacerbate Europe’s slide towards “Japanification”, turning instead to productive sustainable investment – public spending focused on investment – could offer a different outcome. But there is almost no willingness to roll out a fiscal response. A conservative culture exists around budget deficits, especially in core Europe, and the 2013 Fiscal Compact imposed a 3% cap on government deficits. The major economies which need it most are already at or near this limit (Figure 1), but it is necessary to go beyond it to stimulate economic growth.

Figure 1: European government deficits, 2018 (% of GDP)

Source: OECD, 2019

As governments become more sensitive to climate risk, we believe the way to stimulate the economy could be a fiscal response related to social or green projects, mapped to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs).

These provide a salient guide for investing towards a more sustainable world, for investors and governments alike. The 17 goals signpost global development priorities which, if they are to be met, require significant investment in sustainable projects. For example, Oxford Economics has forecasted investment of €11.1 trillion, or about 13% of annual global GDP, will be required by 20402, and specifically sustainable investments of €270 billion3 across the continent are required per annum to meet the European Commission’s energy and climate goals.

Crucially, we think this investment, through net new borrowing, should be carved out of the strict 3% limit. Climate change is high on the list of concerns of the European electorate and the most politically palatable reason to alter the debt rules.

Within this governments could adopt a direct tax and spend approach. The basic premise here is to tax the bad and subside the good. For example, across Europe taxes on diesel are increasing year-on-year, while simultaneously it is not uncommon for governments to subsidise the purchase of an electric vehicle (EV). In Germany, for example, buyers can get a €5,000 subsidy for an EV4/.

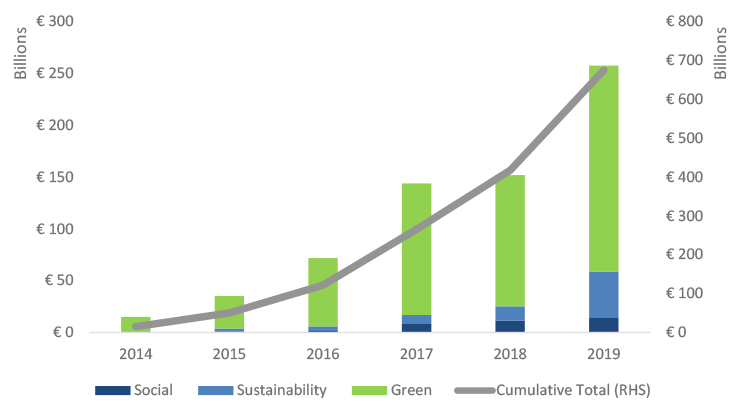

However, such initiatives alone will not stimulate growth over the long-term. Instead, social impact investing is, in our opinion, the vital component, particularly through green, social and sustainability bonds. These are “specific use-of-proceeds” bonds with which the financing is exclusively channelled to pre-identified projects where the outcome will be green, social or sustainable, or a combination of social and green (Figure 2). This has been an undernourished area of issuance, but in the past couple of years there has been an orientation towards financing which targets such outcomes. In fact, 2019 was a record year with more than €250 billion raised through such bonds, and €670 billion raised since 20105. Bonds are a particularly effective tool for measuring impact precisely because there is the capacity and transparency to measure their outcome directly.

Figure 2: Differentiating bond types

Source: Columbia Threadneedle Investments & the ICMA

Tangible examples of such products that could be replicated across Europe are HSBC’s SDG bond, and European Investment Bank’s Sustainability Bond, both of which are mapped to the UN SDGs. For example, the HSBC Bond targets seven of the 17 SDGs: good health and well-being; quality education; clean water and sanitation; affordable and clean energy; industry, innovation and infrastructure; sustainable cities and communities; and climate action.

Specific use-of-proceeds bonds are not exclusive to corporates and supranationals; Belgium, Ireland, France and the Netherlands have issued green bonds in the past two years targeting climate mitigation and adaptation projects. Further expansion is likely this year with Germany, Italy, Sweden and Spain stating their intentions to issue green bonds over the coming months, whereby the use of proceeds will tackle climate change initiatives.

Figure 3: Annual and total specific use-of-proceeds issuance (billions of $)

Source: Bloomberg, 2019

The Europe 2020 Bond Initiative is another good example of how to stimulate capital market financing, and it could be tweaked towards a green focus. The main objective of the initiative is to create the conditions to attract additional private sector financing for individual infrastructure projects. The difficulty with new projects for shareholders is the uncertainty during the construction phase, so to enhance the credit worthiness of such a deal, having the government as a “first loss position” is attractive. Investment could target social housing, health or environmental standards.

Crucially, as monetary policy seems to be reaching its limits, so the market has developed beyond the traditional means of stimulus, beyond, for example, simple bond issuance. New technology means spending can be more targeted.

There has been much debate over the appointment of Christine Lagarde as the European Central Bank’s president, over whether she has the right experience to head the eurozone’s central bank with its responsibility for macroeconomic policy. Perhaps her lack of text book economics could be the catalyst for a fresh perspective on our approach.

Conclusion

Traditional monetary policy in isolation no longer seems to be working in Europe, with the region drifting towards its own decade of stagnation. It is time for a different approach. We believe a focus on green and sustainable policy, carved out of traditional fiscal budgets, can help deliver growth in a way that will not only help the economy, but also society and the environment.