From 31 October – 13 November

world leaders and their delegations

from nearly all countries across the

globe came together to work on the

issue of climate change. We look at

what was achieved over the course of

the conference:1

Major takeaways:

- The ratchet mechanism works: temperature alignment will continue to be wound down towards 1.5 degrees centigrade over subsequent cycles of negotiations – this is a clear indication of the direction of future policy

- The private sector has stepped up: when including all pledges

– net-zero targets and other commitments not currently

incorporated in policy – they add up to an end result of 1.8 degrees

- Carbon markets: rules on international carbon trading have

been established. Loopholes remain so caution is needed

- Civil society is unconvinced: despite COP26 yielding better

results than anyone on the inside expected, protestors and civil society have reacted negatively. Pressure to achieve 1.5 degrees has, if anything, increased. Attention to pledges and especially net-zero commitments will be strong. Companies will face reputational risk if they try to fudge net-zero pledges.

The last-minute games played by the Indian and Chinese delegations got the headlines, but the biggest result to

emerge from this COP (Conference of the Parties) was confirmation that the ratchet mechanism designed under Paris 2015 agreement works – this was its first test and it passed. National pledges wound projected temperatures down by 0.3 degrees and, what is more, those pledges will need to be updated by next year’s COP, accelerating the ratchet mechanism that would normally run on a five-year cycle.

Going into the summit the goal was to

keep the target of 1.5 degrees alive,

and this ratchet acceleration has done

that. No one expected to be able to get

national pledges (known as nationally

determined contributions or NDCs)

down to 1.5 degrees on a single cycle,

so accelerating the next cycle is a

meaningful result.

One overarching takeaway is how the

focus of these meetings has changed

– from 2 degrees and timelines of

2050 to 1.5 degrees and 2030.

This aligns the political discussions

with the science which shows that a

45% decline in emissions is required,

based on 2010 levels, by 2030 in order

to limit temperature rise to 1.5 degrees

(based on 2019 levels this increases

to a 50% decline). Figure 1 shows the

alignment of temperatures against

various tiers of pledges.

Figure 1: alignment of pledges

Temperature rise (degrees centigrade) | |

|---|---|

1.8 | If all NDCs, pledges and

net-zero targets and

corporate pledges agreed

at COP26 are achieved

(optimistic scenario) |

2.1 | NDCs plus the US and

China net-zero targets |

2.4 | NDCs submitted at Paris

2015 only |

2.7 | Current policy (does not

include policy proposals) |

The private sector took on more of

a role than ever before at this year’s

COP, with corporate commitments

on a number of topics. These are

summarised here:

- Deforestation: 130 countries promised to collectively halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030. Countries representing 85% of global forests, including Brazil, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), backed this commitment but scepticism remains around whether it will be delivered. $12 billion in public funds for forests, and more than $7 billion in public-private investments have been committed towards this. Thirty financial institutions with more than $8.7 trillion of global assets committed to eliminate investment in activities linked to deforestation.

- Methane: led by the US and the EU, 109 countries committed to reducing methane emissions by 30% before 2030, including Indonesia, Canada, Brazil, UK, Bahrain, Uruguay, Cuba and Malaysia. China has committed to continue the discussion with the US in the first half of 2022 to focus on the specifics of enhancing measurement and mitigation of methane. Russia is a notable absence.

- Internal Combustion Engines: a group of companies and countries are working towards 100% electric vehicle sales by 2035 in leading markets and 2040 in developing markets. Members include the UK, Canada, Norway, Chile, India and Kenya, along with Ford, General Motors, Jaguar Land Rover , Mercedes-Benz and Volvo.

- Innovation: COP26 saw multiple announcements on innovation in hard-to-abate sectors such as cement, steel and green hydrogen. Some of these are focused on stimulating demand rather than supply, which in turn should encourage existing producers to innovate and increase supply – “if you make it, we will buy it”.

- Oil and gas: the attention is broadening beyond coal, and new initiatives are targeting the supply side as well as demand.

- Coal: underwhelming agreements outside of South Africa’s “just transition” partnership, but the economics are starting to win this battle. For example, even under Donald Trump the US retired the most coal globally and installed the second highest capacity volumes of renewable energy globally after China. The South African mechanism provides a framework to move other coal dependent nations beyond the fuel.

- Asset management aiming for net zero: the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero announced that firms with a combined $130 trillion owned or managed have committed to net zero (through the Net Zero Asset Managers commitment, Net Zero Asset Owners and similar pledges covering nearly every corner of the financial services industry). This figure includes a large amount of doublecounting and has been widely misinterpreted. Nonetheless, it is a huge share of the world’s largest financial institutions committing to net zero – Columbia Threadneedle Investments’ AUM is included in this figure as a signatory of the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative.

Methane pledge – buying time

Relative to CO2, methane has 84x as

much global warming potential over a

20-year time horizon. Cutting methane

rapidly, therefore, gives the world

slightly more wiggle room on carbon.

This is desperately needed as the

latest science outlines that the world

has only eight more years of emissions

at 2019 levels to go before a 1.5 degree

carbon budget is exceeded.

The methane pledge aims for a 30%

reduction by 2030; however, the

International Energy Agency (IEA)

estimates that methane emissions

need to fall by 75% to meet net zero.2

Canada has committed to this punchy

target in the oil and gas sector which,

along with agriculture, are responsible

for the lion’s share of global methane emissions. More than 50% of

methane emissions in the oil and

gas sector can be resolved today

with current technology, while satellite

data is improving the extent to

which these emissions can be

independently tracked.

Article 6 and carbon trading

The rulebook around carbon trading

was finalised at COP26 and part of

this is relevant to corporate carbon

offsetting. These rules still have a

number of loopholes so scrutiny is

likely to remain high. We will keep

an eye on the type of carbon credits

bought by the companies we own –

especially those held in responsible

investment funds.

Carry over of low-quality credits: while

the carry-over of older, less-credible

permits from the Kyoto protocol (called

CERs) will be allowed, the situation

could have been worse. Out of a

potential four billion CER credits, only

320 million will be carried forward and

these will be clearly labelled and easy

to avoid. However, a bigger concern

is that governments could authorise

projects to continue to issue credits

(equivalent to CERs but generated from

2021-2030); but as most of these

projects are wind or hydro-related they

will at least produce clean energy, and

hence avoid emissions and generate

credits, whether or not they are eligible

under Article 6 and do not provide

“additionality”. If all governments

authorise all eligible projects to

transition into the new system under

Article 6, it is estimated 2.8 billion

carbon credits of a very low quality

would enter the system.

Double counting is (almost) out:

Before COP26, Brazil had been arguing

for the ability to double-count carbon credits. What they were suggesting,

to use a hypothetical example, was

that a carbon credit equivalent to a

tonne of carbon dioxide generated by

a forestry project in Brazil and sold

to the UK would count towards both

Brazil’s and the UK’s NDC, reducing

both by one tonne. Brazil stepped away

from this position at COP26, enabling

a conclusion, and it was agreed that

seller countries must account for all

units that are transferred to other

countries, preventing the possibility

of double counting.

However, under the carbon trading

mechanism, as opposed to bilateral

trading, there is an option for countries

to issue non-authorised credits

for “other international mitigation

purposes”, ie voluntary carbon markets

which would not be subject to the

carbon accounting adjustments to

eliminate double counting. There

was heavy debate around how this

class of credit should be used and

how much it contributes to corporate

greenwashing, with countries such as

Switzerland calling for stronger rules.

Ultimately, companies using authorised

credits towards their net-zero targets

will be seen as more credible than

those using non-authorised credits.

It will be interesting to see if carbon

credit pricing deviates according to

quality once this mechanism is fully

established, with a small number of

carbon credit rating agencies already

in existence.

Voluntary retirement of carbon

credits: it was agreed that bilateral

carbon trades between countries for

use in NDCs will only need to retire

credits on a voluntary basis. This is

weaker than hoped as cancellation of a

portion of emissions would mean more

than one tonne of carbon credits would

be required to offset one tonne of actual emissions – meaning an overall

net emission reduction. However, the

carbon trading mechanism covered in

another area of Article 6, and the area

most relevant to the private sector, will

be subject to a mandatory retirement

of 2%. Another rule impacting the

trading mechanism, but not bilateral

trades, is that 5% of proceeds from

trades under the mechanism must

be transferred to an Adaptation fund

to finance adaptation or resilience

projects in the countries already most

vulnerable to climate change.

Innovation in hard-to-abate sectors – The Glasgow Breakthrough Agenda

- Hydrogen: the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) and the Sustainable Markets Initiative (SMI) announced pledges of 28 companies to drive growth in the demand for, and supply of, hydrogen. This can be in four categories: supply, demand, financial support or technological support. On the demand side pledges add up to 1.6 million tons per annum (mtpa) of low-carbon hydrogen to replace grey hydrogen which is currently used in the chemical industry and refining. On the supply side the pledges add up to 18 mtpa of low-carbon hydrogen. In emissions terms this would save the equivalent of the annual emissions of Netherlands and Tunisia combined. Also, African and Latin American green hydrogen alliances are aiming to accelerate green hydrogen adoption in those areas. Namibia has already made progress with the Dutch, Belgian and German governments, with Germany committing to provide €40 million.

- Steel and cement: The UK and India led the Industrial Deep Decarbonisation Initiative (IDDI), alongside Canada and Germany, which aims to drive demand for “green” steel and green cement which will in turn accelerate supply. Currently, cement and steel each account for around 7% of energyrelated emissions globally but do not have easy decarbonisation options. This is because the high temperatures required are harder (but not impossible) to achieve via electricity rather than fossil fuel energy. The most common process of steelmaking also uses coal as a reagent, although it is possible to use hydrogen. The initiative will work to set criteria for green cement and steel, encourage greater transparency and traceability and look to set a globally recognised target for public procurement of green steel and cement. Member governments also committed to the disclosure of embodied carbon of major public construction by no later than 2025.3

- Steel, trucking, shipping, aviation, cement, aluminium, chemicals and direct air capture: The first movers coalition is a US-led coalition of corporates to stimulate clean tech demand for hard-to-decarbonise areas which will in turn incentivise supply. Its statement said: “Members will use their global purchasing power to create new markets for these emerging technologies. These new demand signals empower suppliers to develop and scale their innovations between now and 2030 – helping us to reach our global emission targets.”.4

- Shipping: there were three announcements/initiatives of note. More than 200 businesses have committed to scale and commercialise zero-emissions shipping vessels and fuels by 2030. In turn, nine blue chip companies have committed to shift 100% of their ocean freight to zero carbon options by 2040, including Amazon, Ikea, Michelin and Unilever. Finally, 19 countries have signed the Clydebank declaration to support the establishment of six zero-emission shipping routes by the middle of this decade with more by 2030. With the International Maritime Organisation meeting in less than two weeks to negotiate emissions standards, this is a positive move that should pave the way for productive talks.

The focus moves beyond coal

Outside of corporate pledges, the

final text of the Glasgow Climate

Pact references the phase-down of

inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.

This had already been announced by

the G20, but giving the commitment

a global stage adds emphasis and

scope for further debate. However,

the term “inefficient” provides a lot

of flexibility for nations, including the

UK, which are not ready to phase

these subsidies out yet. Currently,

fossil fuel subsidies amount to around

half a trillion dollars per year – far

outstripping subsidies for renewables.

A “Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance”

also emerged, with Denmark, Wales,

Costa Rica, California, France, Sweden,

Greenland, New Zealand, Portugal and Quebec signing up. The commitment

involves ending new exploration permits

for oil and gas. None of these nations

are major producers, so this will not

drive any significant impact, but it

shows the pressure that governments

are under to address the supply side

instead of focusing purely on demand

reduction. This is obviously not the

optimum tactic when considering

recent energy price volatility but, as

we have previously written, we are

in for a bumpy ride to net zero.

Finally, more than 30 countries

and financial institutions signed a

statement committing to halting all

direct public financing for fossil fuel

development overseas by the end

of 2022 and diverting the spending

to green energy. This comes hot on

the heels of a similar announcement

ending public financing for coal.

Canada signed up, which is significant

as the largest funder of fossil fuels

in the G20, as did the US, the UK

and Germany. The commitment has

the potential to shift $23.6 billion of

fossil fuel investment to clean energy.5

However, Japan, Korea and China are

the biggest providers of this finance

globally and have not yet signed the

wider fossil fuel agreement. A report by Climate Analytics was released

to coincide with COP, which outlines

that by 2030 gas will be responsible

for 70% of the projected increase in

fossil CO2 emissions and 60% of the

methane. Expect attention to intensify

on this transition fuel.

An innovative “just transition” coal

phase-out partnership with South

Africa was announced,6 which will

provide $8.5 billion to support South

Africa in moving to clean energy while

aiming to avoid the negative social

implications of shutting down a major

industry. The country has one of the

most coal-intensive grids globally

and an economy heavily dependent

on the fossil fuel. This could work

as a template for other regions and

discussions have already begun with

countries like Indonesia.

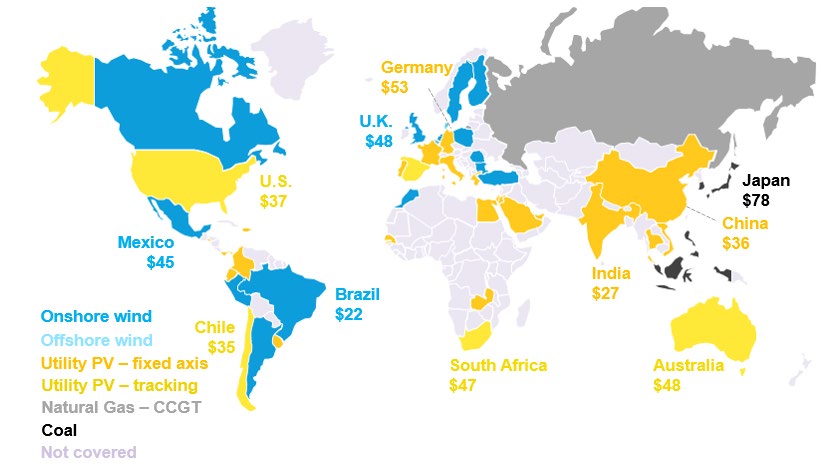

Leading technologies for new bulk

electricity generation are shown

in Figure 2 by geography, with

renewables leading the way in

countries representing more than

two-thirds of the world population

and 91% of electricity generation.

Similar mechanisms to South Africa’s

will be needed to support a just

transition away from coal.

Figure 2: Cheapest source of bulk generation, H1 2021.

Source: BloombergNEF. Note: The map shows the technology with the lowest levelised cost of energy (LCOE) for new-build plants in each country where BNEF has data.

The dollar numbers denote the per-MWh benchmark levelised-cost of the cheapest technology. All LCOEs are in nominal terms. Calculations exclude subsidies, tax credit or grid connection costs.

CCGT = combined-cycle gas turbine.

Net-zero pledges

Scrutiny of dodgy net-zero targets is

increasing, and will continue to do so.

“More than 80% of global GDP – and

77% of global greenhouse gases –

are now covered by a national net-zero

target, up from 68% and 61% last year”,

according to a new tracker co-led by

the University of Oxford.7 “That number

shrinks to 10% of global GDP and

5% of global emissions if only strong

commitments and clear plans are

included.”8

The US published its plan during

COP26 to achieve net zero,9 with

the UK doing likewise in the run up

to COP.10 These add credibility and

pave the way for other nations and

corporations to follow suit.

As this happens, expect to see the

University of Oxford’s 10% GDP and

5% emissions of credible targets start

to close the gap to the 80%/77%

announced. The UN has also

announced an oversight body for

net-zero targets.11