Last week was a big one for central banks in the US and UK. Both raised rates by 75 bps but the background was very different with the result that 2-year rates rose by 24 bps in the US but fell by 19 bps in the UK – a most unusual pattern.

The US Fed was at pains to dispel the market’s hopes that they would soon pivot to lower rates. Instead, rates might rise further and stay higher for longer than the markets had been expecting. By contrast the Bank of England (BoE) predicted an extended recession and forecast that inflation end up below their 2% target if base rates followed market expectations.

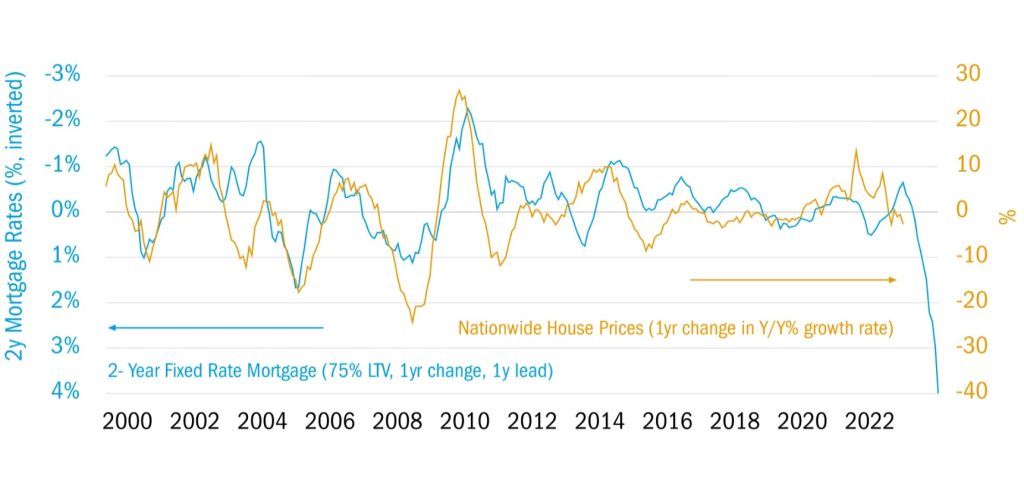

Despite the BoE’s dovishness, mortgage rates have risen steeply in the UK since September. The implications for the direction of house prices are clear: after years, indeed decades of strength, prices are headed lower. But the scale of the decline is highly uncertain. Our best guess is that the fall will be significant and extended. Interest rates in the UK, and globally have been on a volatile but generally downward path since 1980. With aspirations for home ownership so strong, that fall in mortgage rates has been roughly discounted into higher house prices. According to this argument, if interest rates halve, house prices almost double even if the decline is accompanied by lower inflation. It’s all about cash flow constraints on mortgage-financed house purchase. Now we think that the era of ultra-low interest rates is behind us.

Rising mortgage rates could hit house prices hard

Source: Macrobond, Columbia Threadneedle and Bloomberg as 0f 04/22/22

The chart shows a reasonably close relationship between the change in mortgage rates and the change in house price inflation a year later. Extrapolating the lines might suggest we are in for a collapse in house prices. I do not think prices will fall that far or that fast, but it does serve to highlight the prospective weakness in the housing market. In addition to higher mortgage rates, there is also the squeeze on real incomes from declining real wages, higher taxes, and lower government spending. But there are many positives for housing. Mortgage borrowers and lenders are much less geared than in past housing recessions, unemployment is low and although mortgage rates have risen steeply, they remain low in absolute terms. Moreover, after the surge in rates after the Kwasi Kwarteng budget, expectations for base rates have fallen so mortgage rates are starting to ease back down.

What does all this mean for the overall economy? First, the weaknesses in UK growth versus the US are exacerbated by our massive current account deficit so I expect sterling to remain weak. Second, the weakness in housing will depress overall economic activity so the bleak outlook presented by the BoE is one we share. This will limit the rise in base rates. But despite the prospect of a tough budget by the new government, a big fiscal deficit will remain. In addition, the BoE must sell the massive stock of gilts that they bought as part of Quantitative Easing plus the ultra-long gilts they bought as part of the emergency support programme.

It is not all doom and gloom though. The UK economy will adjust, inflation will come down and we will return to growth. Risk assets – like equities – are in for a tough time and they may start 2023 on a weak footing but I’m expecting the bull market to resume as the year unfolds.