The transition away from fossil fuels was never going to be easy and in 2021 we hit the first bump on the road of this journey. Rocketing energy bills have affected most countries as the price of oil, coal and gas has soared over the past year. There have been several factors behind this crisis, but at its core it is a demand versus supply mismatch.

Demand for fossil fuels recovered swiftly as Covid-19 lockdowns were relaxed. Simultaneously, rising renewable energy within the total global energy mix has contributed towards greater variability in energy generation – the sun doesn’t always shine and the wind doesn’t always blow, with the UK for example seeing some of the lowest levels of wind in 70 years in 2021.

This, combined with droughts in Latin America affecting hydropower output in the region, which accounts for 45% of its total electricity generation, led to increased demand for fossil fuels. But investment into oil and gas has been low in recent years with weak commodity prices and environmental, social and governance (ESG) related concerns limiting capital inflows into the industry. More recently, supply chain challenges have impacted production. Supply simply couldn’t keep up with demand and so prices squeezed higher.

We believe this energy crisis, along with rising global geopolitical tensions – including the tragedy we are seeing in Ukraine – will if anything accelerate investment into renewable energy and the technologies needed to make renewable sources more reliable, such as battery storage and green hydrogen. However, more careful planning and balancing of the energy grid will be required as renewables start to exceed 30% of global electricity generation. In addition, economies need to do a better job of winding down demand for fossil fuels. We still consume far too many, with global oil demand forecasted to not peak for another five to 15 years. You can’t start closing the taps when you’re still thirsty. But energy-related transmissions in transportation, across industries and in heating account for 78% of global emissions. If we have any hope of achieving net-zero targets it is vital we transition to clean energy.

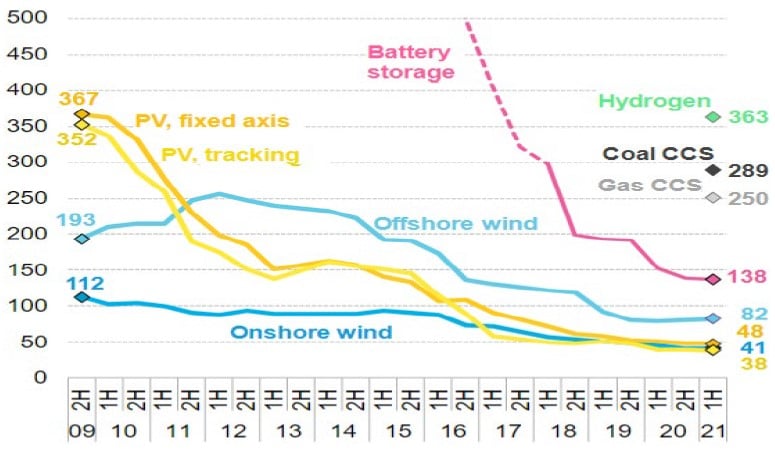

Put another way, currently only 17% of our total energy supplies come from clean energy – this must rise to 78% by 2050 if we are to achieve our net-zero aims2. Increasingly, the transition to clean energy also makes economic sense. Renewables are now the cheapest form of new electricity generation across about 90% of the world by energy supply with the recent surge in fossil fuel prices further improving their relative cost competitiveness (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Levelised cost of energy (LCOE) for selected low-carbon power technologies ($/MWH)

Source: Systems Change Lab; Climate Watch 2021, IRENA 2021b, Systems Change Lab June 2021.

Once you factor in the economic costs of unabated climate change, forecast at more than 3% of GDP being lost every single year by 2030 3, the clean energy transition becomes even more attractive. And although the large capital investment required is inflationary in the near term, over the long term transitioning to renewables means governments and companies will no longer be exposed to the volatility of commodity pricing. With 80% of people living in countries that are net importers of fossil fuels, this has huge social benefits as renewables provide a cheap source of energy. Attractive economics, the electrification of economies and increasing government policy and consumer support are a powerful cocktail to accelerate investment into renewable energy. In fact, the IEA (International Energy Agency) forecast that by 2026 global renewable electricity capacity will rise more than 60% from 2020 levels to more than 4,800GW, with renewables set to account for almost 95% of the increase in global power capacity through to 2026 – this is equivalent to the total current global power capacity of fossil fuels and nuclear combined.4 Transitions are not easy, but it doesn’t mean they don’t happen. We have undergone previous energy transitions – in the 1800s the shift away from whale oil was equally inflationary as supply was cut faster than demand fell, but it didn’t stop the transition to a superior energy technology, which at that time was petroleum. We believe the same to be true for green energy.